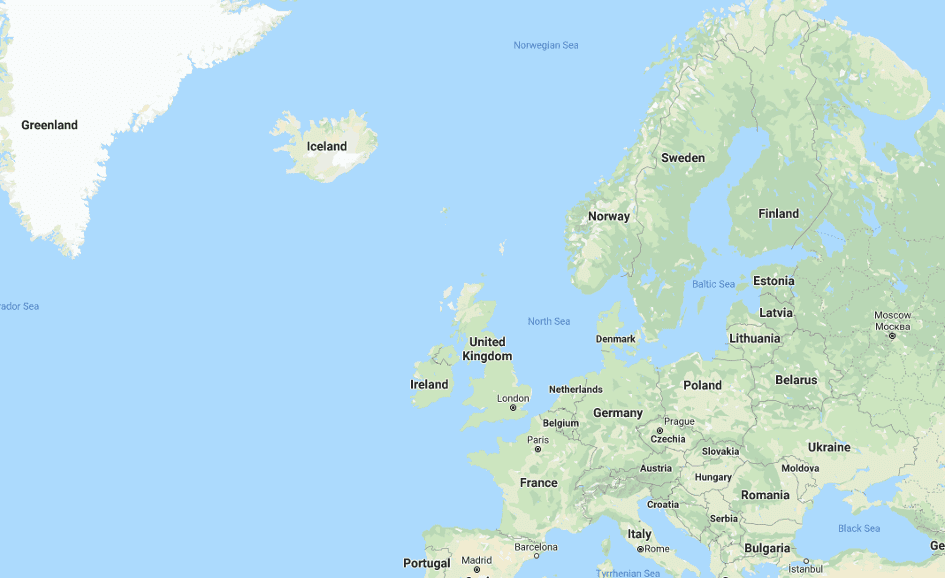

Iceland is a country with a rich history. From the Settlement of the true Vikings, the country being under a foreign rule, to the independence again.

Settlement (870-930)

Iceland was founded during the Viking Age. Norsemen from Scandinavia and Celts from the British Isles first settled in Iceland, or how it then was described Thule.

The first permanent settler of Iceland was Ingólfur Arnarson, a chieftain from Norway. He settled together with his family in 874 AD. He named the ‘town’ Reykjavik. Sounds familiar? You can find Arnarson’s statue on the Arnarhóll, close to Harpa concert Hall and at the end of Laugavegur street. Want to see more of Reykjavik have a look at our city walk tours.

The first settlers of Iceland were mainly farmers and/or chieftains that were dissatisfied with the outrageous policy of King Harald I. They sailed from Norway, the British Isles and other Scandinavian countries to Iceland with their families, serfs and cattle. They established themselves by breeding cattle and fishing.

In the beginning, there was no central administration, nor a government. Early settlers had continued to use the Norwegian laws and district-wide legal assemblies called Þing (Thing), led by the chieftains. These local assemblies were held regularly in spring and autumn.

Commonwealth (930-1262)

In 930 AD the Icelandic Parliament and the first democracy in the world were established in Þingvellir (Thingvellir). Thingvellir is nowadays a geological National Park where you can witness the Eurasian tectonic plate and the North American tectonic plate drifting apart. It is located on the Golden Circle.

In 930 AD a constitution was adopted for the whole land, based on the Norwegian constitution. The parliament was both a legislative and a judiciary and gathered annually in midsummer for 14 days. During the gatherings, the laws were formulated, reviewed and amended by The Law Council which consisted of the different chieftains and their advisors. The Law-speaker, elected by the Law Council, had to memorise the law and quote it. The Law-speaker was chosen until 1117 AD, from then on the laws were written down. When the laws were being recited, it was mandatory for the tribal chief to be present.

The establishment of the Parliament marks the beginning of the independent republic of Iceland. This period of governance is known as “The Commonwealth” or “The Golden Age of Iceland”. Another nickname for this period was “The Saga Age”. Loads of events that were written down in the Icelandic sagas (that date back to the 12th and 13th centuries) took place during ‘The Golden Age”. Moreover, many events described in the sagas did happen at Þingvellir.

In the years 999-1000 Christianity made its entrance in Iceland. The first bishopric was founded in Skáholt in 1082, but the second and most influential bishopric was established at Hólar. The first bishop Jón Ögmundsson was determined to eradicate all traces of paganism, the religion where people worship nature. He succeeded in this by, inter alia, changing the names of the days (that were named after pagan gods). In addition, he forbade dancing and writing love poems.

In the Great Age of Writing (1120-1230), as the name suggests, remarkable literary achievements were made. Most of the Icelandic sagas were written during this time, including the great historical works: Íslendingabók (The first national history book) and Heimskringla (The History of Norwegian Kings). The great part is that we Icelanders can still read these stories. This is due to the fact that our language has evolved little over the centuries.

Iceland went through a turbulent period during “The Age of the Sturlungs” that started in the year 1220. The Sturlungs were members of the most powerful family clan. The most famous family member was Snorri Sturluson. Through marriages and political alliances, the Sturlungs were dominating a great part of the country. Of course, there were tribal chiefs and other well-known families, who could not appreciate their influence. It led to feuds and wars between the different chieftaincies that caused economic and social ruin. The Norwegian King Háklon Hákonarson saw his chance to broaden his power in Iceland and unite all Norwegian Viking Age settlements. The king succeeded in his mission, by making several of the greatest Icelandic chieftains his liegemen and by persuading other chieftains to swear allegiance to him, after killing rival Snorri Sturluson in Reykholt. The people of Iceland hoped that this would bring peace to the country, but it also meant the end of the Icelandic Commonwealth period and independence.

Iceland under Foreign Rule

This was the start of centuries of poverty, death and just hard life.

Under the Norwegian crown, the Icelanders became dependent on Norwegian ships for supplies, which often failed to arrive, due to the fjords and other access routes to the sea that were blocked by ice. Additionally, destructive volcanic eruptions, recurring epidemics and famine plagued the whole country. In 1349 the Black Death hit Norway. The result was that all trade and other provisions were cut off.

In 1380, the Norwegian monarchy entered into an alliance with Denmark; however, this change did not affect Iceland’s status. After Norway and Denmark formed the Union of Kalmar together with Sweden in 1397, Iceland came under the ruling Danish crown. From then, conditions in Iceland went from bad to worse. Icelandic chieftains were replaced by Danish royal officials. The parliament became a court of law, where judges were chosen by royal officials.

In the early 15th century, Iceland was hit by the Black Death. It killed more than a third of the population.

The Danish crown oppressed, even more, the local population of Iceland by killing the last catholic bishop and imposing Lutheranism. Also, by establishing a trade monopoly, which prohibited Iceland from trading with countries, other than Denmark. The result is extreme poverty among the people of Iceland. The Danish trade monopoly lasted until 1787. A third change was on a constitutional level. The absolute monarchy was established in Iceland and the power of the parliament decreased significantly.

In 1703, the first census was taken in Iceland, the population was 50,366 and about 20 % were destitute. The population declined several times during this century, because of epidemics, natural catastrophes and enormous poverty. For example, in 1707, about 18,000 people died because of smallpox. The destructive volcano eruptions of Katla in 1755, and foremost Laki in 1783 caused floods, ash and toxic fumes ensuing famine. It killed more than 10,000 people. As you can see, during the 18th century the census went far under 40,000 people twice.

Returning towards Independency

In 1800 the parliament was abolished by royal decree and later replaced by the Supreme Court. By the middle of the 19th century, however, a new national consciousness was reviving in Iceland, and Jón Sigurðsson had become the great leader of the Icelandic independence movement. In 1843, the parliament was re-established as a consultative body, but only a few powerful feudal barons and landowners were elected. When in 1848 king Frederick VII of Denmark resigned from his absolute power. The question was, what the status of Iceland would be in the new form of government. Jón Sigurðsson’s opinion was that the Danish king could only return his absolute power over Iceland to the Icelandic people themselves, as they were the ones who had relinquished it to the Danish crown in 1662.

Finally, in 1854 the trade ban with other countries was abandoned. In 1855, freedom of the press was established. In 1874 the millennium celebrations of the settlement were held and King Christian IX of Denmark came to visit Iceland. He gave a new constitution, which gave the parliament legislative powers in domestic affairs. The constitution was changed in 1904, and Iceland came under Danish rule. The first Icelandic minister was installed in Reykjavik.

While the years of self-government, 1904-1918, were characterised by improvement in the economic and social fields, Iceland’s quest for greater autonomy continued. On 1 December 1918, Iceland became a sovereign state, the Kingdom of Iceland, in personal union with the King of Denmark.

Festivities were held in 1930 at Thingvellir to celebrate the Millenium anniversary of the parliament. The festivities were attended by more than 30,000-40,000 Icelandic people. You could say that almost all of the Icelandic people were present at this celebration.

A new era in Iceland’s history began in the year 1944. This was the year that Iceland broke its union with Denmark. The Republic of Iceland was founded in, as you can guess, Thingvellir. The national day that was chosen is 17th June, the birthday of Jón Sigurðsson, one of the national heroes of the country and the great leader of the independence movement.

After seven centuries of foreign domination and oppression, Iceland is a republic on its own.